What’s a 701?

Corning Glass Works perfecting the mix of what would become known as Pyrex in 1915, and power insulators were a prime application. Corning believed that Pyrex glasses provided superior properties to the porcelain conventionally used in power insulators of the era. The glass offering low thermal expansion and low temperature rise in the sun, so that thermal cycling would not cause pins, caps and cement (in the case of suspension types) or tie wires to work lose. They had excellent thermal shock resistance, so as to not break, crack or shatter due to the heat of flashovers. Glass offered uniform quality, since it could be visually inspected for voids, and non-porosity, so it would not to absorb water or contaminants that would degrade its insulating properties.

Pyrex power insulators eventually came in a wide variety of sizes, and were known to be used in 45 US states and at least 10 countries. Initially, the first Pyrex offerings were suspension insulators in 1920-1922. These glass disks, eventually made in 6″, 9″, and 10″ sizes, are linked together to provide the insulating voltage required and support conductors under a crossarm or where the conductors dead-end into a pole. In 1923, they added the “stacker”, a three-piece insulator over a long wooden pin to be used on Montana Power Company’s 50-60kV lines. (CD 248 / 311 / 311 to collectors.) By 1927, the line had been expanded to include a wide variety of pin-types, covering both power insulators for voltages from 6.6kV up to 60kV as well as carrier-circuit communications insulators (CD 128). Pyrex power insulator manufacturing came to an end in 1945, with the CD 128 communications insulators hanging on a few more years into 1951.1

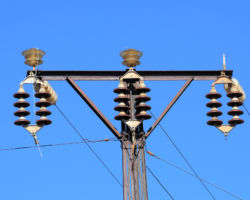

The big daddy of them all was the Pyrex 701, a 38-pound, 70kV monster of an insulator. Introduced in 1930, these are known insulator collectors as CD 331s and are the pinnacle of US glass pintype power insulator technology. They are the largest single-piece glass pin type insulators ever made anywhere in the world. (At least that we know of… Anything above 70kV almost always went with suspension insulators.) The 701s were largely used in the Pacific Northwest 2 & 3, with another small group used in Massachusetts and Connecticut on some 69kV feeder lines. 4 & 5

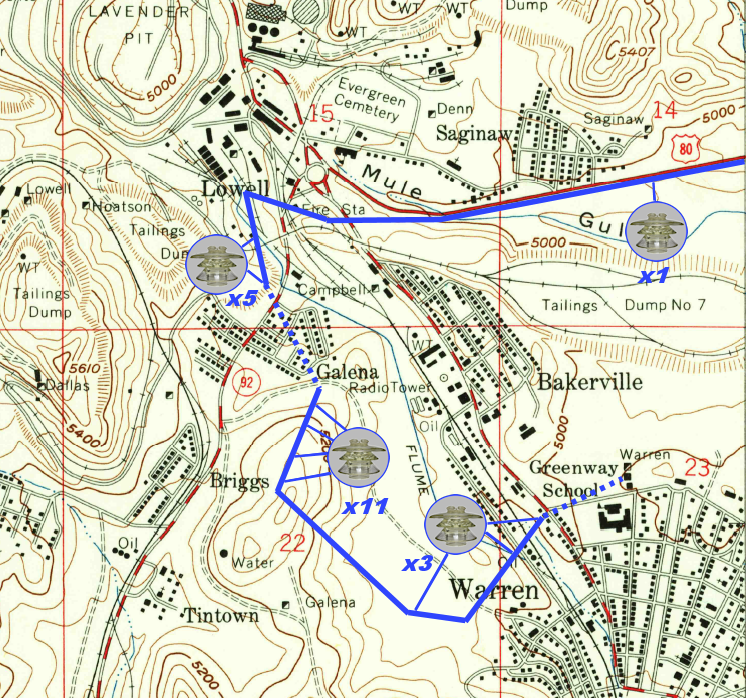

The only place I know that the big 701s can still be seen in the air today is around Bisbee, AZ. So on my way back from the Tuscon, AZ, insulator show in early February 2022, I decided to detour on my trip home to see how many of these jewels were still in the air.

About the Lines

Bisbee is, of course, famous for its copper mining history. The history and the connection between all the companies is long and drawn out, as one would expect, and could easily fill a book. For those interested, I strongly recommend exploring the Bisbee Mining & Minerals website. I found it highly useful in trying to understand the history of many of the shafts and companies.

Copper was discovered in 1877, and soon underground mines popped up everywhere. What followed was a flurry of not only mining, but corporate consolidation. Eventually, the Phelps Dodge mining company became the dominant player through their subsidiary, the Copper Queen Consolidated Mining Company. The other main players – the Calumet & Arizona Mining Company and the Shattuck Denn Mining Company – would be swallowed up by PD in 1931 and 1947 respectively, leaving Phelps as the only major player. Copper extraction continued until 1975, when depressed prices and decreasing ore grade stopped operations.

So how does this all relate to insulators in 2022? Let’s rewind the clock to 1917. Early in development of the mines around Bisbee, the Copper Queen Consolidated Mining Company (CQCMC, aka Phelps Dodge) had maintained power stations at each of their shafts. 6 However, that was inefficient, as a central power station could provide for the needs of all the hoists and ventilation fans with less equipment and less labor. A new central power station for the Copper Queen operations was established on the side of Sacramento Hill.7 Each of the shafts and their associated hoists and ventilators were then knitted together with a grid of transmission lines owned by the mine.

In order to go after a large body of lower grade ore beneath, Phelps Dodge began removing Sacramento Hill in 1917 with the intention of building an open pit mine – the aptly named Sacramento Pit. As the power plant was in the way, it would need to be removed and a new source of electrical power established. The Copper Queen had moved smelting operations out of the Bisbee area to Douglas, AZ, in 1904, and smelting sulfide ore creates a great deal of waste heat – heat that could be used to boil water and turn turbines attached to generators. A new ~20 mile steel-towered line was constructed to carry 4 megawatts of power from the Douglas smelter to Bisbee (or at least Lowell), reported to be in operation by December 1919. In addition, a backup source of power was installed at Bisbee, consisting of two 4-cylinder, 2000hp diesels driving two 60Hz, 3 phase, 1.5MW generators, and two additional 5-cylinder 1250hp diesels driving two 60Hz, 3 phase, 850kW generators.8 (Based on pictures of the generators, these appear to be the ones installed at Lowell, near the Junction shaft.)

Pyrex 701s in 2022

The lines today appear to be disused, as they weren’t part of the public power system but just PD’s private plant system. (Note this isn’t the same as dead – they may still be powered from the end I can’t see, or picking up voltage from induction.)

I believe this main 1919 line is the one whose remains can be still be found along Arizona Highway 80 today, leading out from the facilities at Lowell / Junction. The steel tower construction style is consistent with lines of that era. Everything past the end of Tailings Pile #7 (the big tailings pile from the pit, where Arizona St. from Warren comes in to 80) to Douglas is now gone. Presumably it was removed when the smelter shut down in 1987 or shortly afterwards. There’s a stub feeder that branches off just south of the Saginaw shaft along Hwy 80 just out of town that’s devoid of wire.

Extending from the Lowell substation are lines of similar steel construction branching off to the Campbell shaft and south through Galena, going through several more switching stations and eventually winding around to the Warren shaft. Presumably other facilities were also connected, but between mining and reclamation work, no other remnants could be located from either aerial photos or from public roads. For the leg going south out of Lowell, the section of the line crossing Highway 92 and through the residential area has been removed. On the other end, the section from Bisbee Road in Warren to the Warren shaft facilities is likewise gone.

Since Pyrex 701s would not have been in production when at least the main Douglas line was built, I suspect that they’re later replacements or were used when the lines were extended/upgraded. Likewise for the Pyrex suspension insulators that are seen all over the system. They’re also all clear glass, despite the appearance. They just have a healthy coating of pollution and dirt on them.

I count 20 Pyrex 701s that still exist today in the air today. If you go look on your own, here’s the summary:

- 1x along Highway 80, where the feeder line to the Saginaw shaft came off the Douglas-Lowell line.

- 5x between Lowell and Highway 92, in the Freeport-McMoran yard. The line is cut where it would have passed over 92 and through the Galena residential neighborhood.

- 11x on four poles climbing up the hill south of Galena, visible from School Terrace Road east of Hwy 92 (incidentally the road is the former interurban electric railway grade)

- 3x coming down off the hill behind the school into Warren. One is high on the hillside behind some houses, one is on a pole south of Cochise Row, and one is on a pole north between Cochise Row and Bisbee Road, adjacent to the old railroad grade.

There may be more up towards the Galena shaft on the hill west of Warren, or some up towards the Dallas shaft, but they’re deep within private property and not accessible. At least not that I could find.

I would love to have a full diagram of the Phelps Dodge power system for the Bisbee-Douglas-Nacozari system, but without somebody who has access to the company archives (now Freeport McMoran), I’m unlikely to get one if such a thing even still exists. If you’re a local and have historic pictures of some of these lines, I’d love to see them as well and update this article.

Sources

- John & Carol McDougald, “Insulators: A History & Guide to North American Glass Pintype Insulators Volume 1“, pp 129-132

- Hyve, H. G. “Bea” (aka Clarice Gordon), “701’s in Service,” Insulators: Crown Jewels of the Wire, November 1975, pp 2-3

- Geographical Locations of Glass Insulator Usage in North America, https://www.insulators.info/insulator_geography/

- Kaminsky, Jeff, “CD 331 — PYREX 701,” Insulators: Crown Jewels of the Wire, April 1989, pp 19-21

- Kaminsky, Jeff, “Porcelain 701’s,” Insulators: Crown Jewels of the Wire, June 1990, pp 14-17

- “Review of Mining“, Mining and Scientific Press, November 15, 1919, p 717

- “Moving a Hill,” Literary Digest, Jan 8, 1921, p31, quoting an article from The Mining and Scientific Press

- Electrical World, June 16, 1923, p 1405