This is the story of a lowly, smelly rock that now sits on a shelf in my living room, and the tale it can tell. It’s a tangible link to a tale that spans 120 years, telling a story that weaves together American industry and capitalism at the dawn of the 20th century, an isolated ore-hauling railroad in Alaska, shipwrecks and piracy on the high seas, salvage rights, and reality television into one single narrative.

Huh? Just go ahead and pause until your brain works through that last sentence. Then read on.

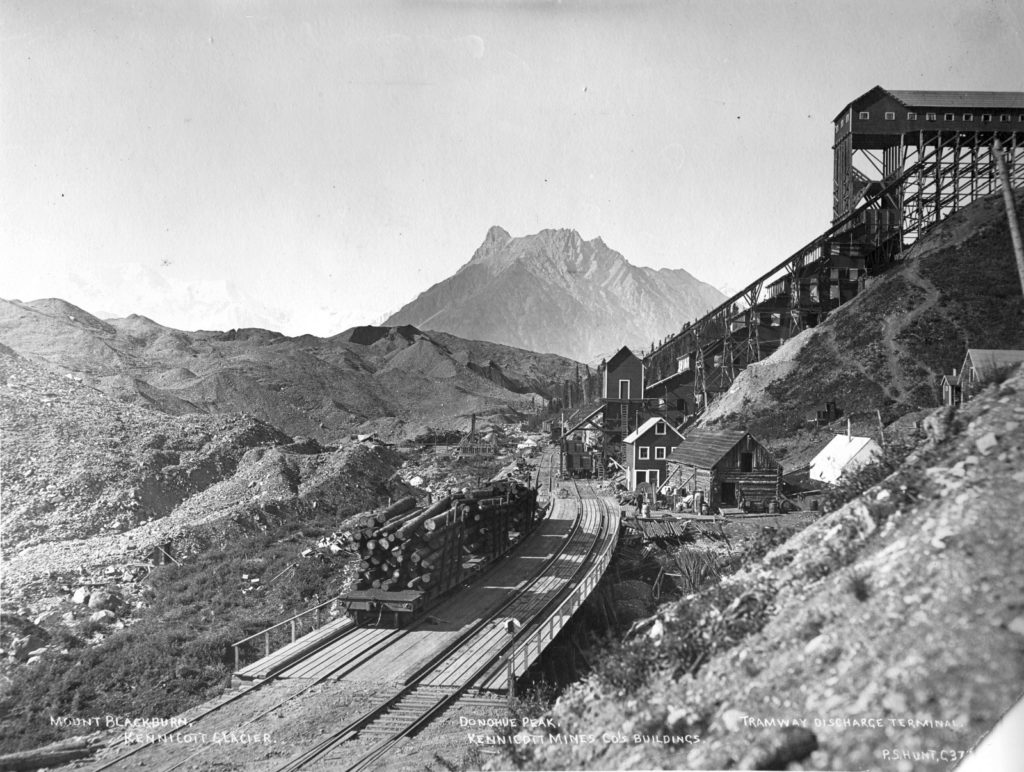

Where it All Began – Kennecott, Alaska

Our story really begins with the exploration of Alaska’s Copper River country around 1885 by Lt. Henry Allen, extending northward from an 1884 expedition by Lt. William Abercrombie. Allen reached the juncture of the Copper and Chitina rivers, and there met with the Taral Band of the Ahtna people – the native inhabitants of the area (and also the word for the Copper River, apparently). His official mission, in addition to exploration, was to “assess the alleged hostility of the natives.” During his visit to Taral (the native village just downstream from modern day Chitina), he noted that many of the people were using copper tools and utensils.

In 1899, Abercrombie led a follow-up expedition up the Copper River valley. While the mission was primarily military, searching for a route to the Yukon River that didn’t pass through Canada, the expedition attracted a number of prospectors seeking mineral wealth. Prospectors from the McClellan Group found the Ahtna at Taral in a state of starvation, and traded knowledge of a food cache along the Bremner River for information about the copper deposit. Upon being led to the deposits, about 10 miles east of the big deposits above what would become Kennecott, initial assay results showed the ore to be 60-70% pure copper. Three claims were staked for the McClellan party in July 1899.

The follwoing year, two prospectors from the McClellan group – Clarence Warner & Jack Smith – returned to the area to more fully prospect and assess the potential of the deposit. On July 22, they spotted a green patch high on a mountainside – far above where any grass should grow. They’d just discovered the vein that would become the Bonanza Mine – the richest copper ore body known in the world at that time.

The claims came to the attention of one Stephen Birch, a recently graduated mining engineer sent to Alaska in search of investment opportunities for the Havemeyer family. Birch initially purchased a 5.5% stake, but with the backing of the Havemeyers eventually negotiated purchase of all of the claims and fight off a number of legal disputes along the way. Thus began the Alaska Copper Company in 1902.

Despite the richness of the ore body and the obvious value contained within, the fundamental problem remained – the ore was located high on a mountainside in an inhospitable climate, hundreds of miles from reliable transportation and thousands of miles from a smelter. Birch went on to seek investment from some of the wealthiest men of the time – the Guggenheims and JP Morgan – to form the Alaska Syndicate in 1906. Finally the effort was adequately capitalized to build all the supporting infrastructure it out need – a mine, a railway to tidewater, and an ocean-going steamship line to haul the ore to smelters in the lower 48. With this was born the Kennecott Mine, the Copper River & Northwestern Railway, and the Alaska Steamship Company, all neatly under the control of the Syndicate.

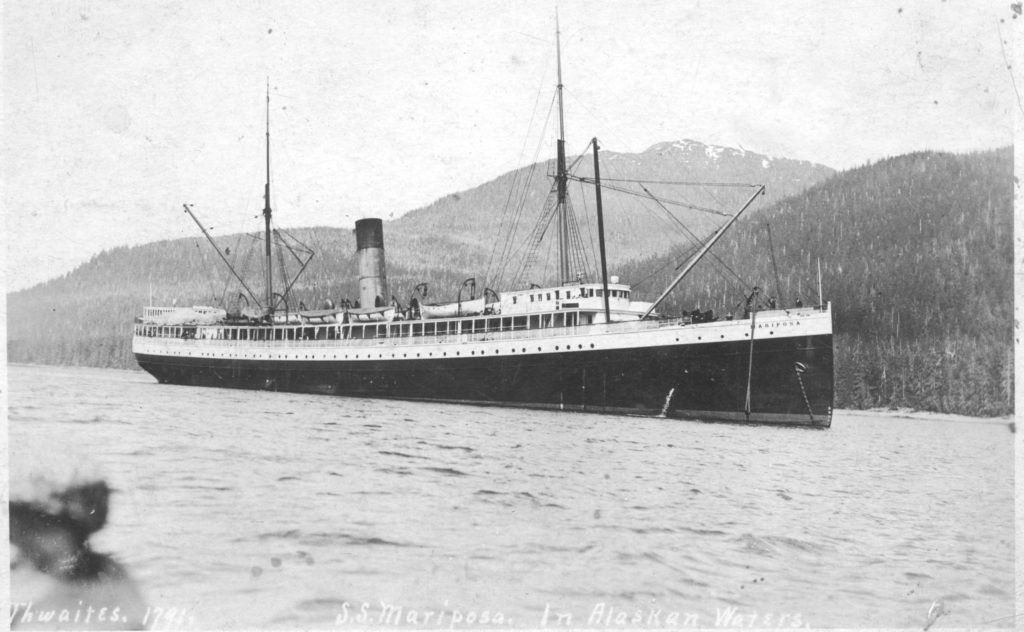

The Ship – the SS Mariposa

The SS Mariposa was a 3150-ton, 314-foot steamship built in Philadelphia in 1883 for the Oceanic Steamship Company. She was originally built to haul passengers and cargo from San Francisco to Hawaii, and later on to Australia and New Zealand. In 1912, she was sold to the Alaska Steamship Company and operated between the west coast of the Lower 48 and various Alaskan ports. The Alaska Steamship Company, like the railway and the mine, was under the control of the Alaska Syndicate – the large conglomerate founded by JP Morgan and Daniel Guggenheim in 1906 to tap the copper reserves near McCarthy / Kennecott. As such, one of the ship’s regular ports of call was Cordova, AK, where it would pick up loads of copper ore from the CR&NW railroad dock to haul to the smelter at Tacoma, WA.

The waters of the Inside Passage were quite treacherous in that era, with many unmapped sharp underwater reefs and seamounts in otherwise deep waters. Many ships wound up having remarkably short lifespans running those routes, and shipwrecks were frighteningly common. However, the route saved hundreds of miles and protected vessels from the hazards of the open ocean, so most traffic to southeast Alaska took advantage of it.

To give you some idea how hazardous these waters could be, the Mariposa hit a rock for the first time on October 8, 1915, near Bella Bella, BC – one of 45 reported shipwrecks in the waters off the coast of Alaska and British Columbia that year. The wreck was relatively close to shore, and the ship never submerged beneath the waters. Within a short time, it was successfully refloated and towed to Seattle for repairs. That’s not the wreck of interest, however – it’s just the first one.

The wreck of this tale happened just two years later, on November 18, 1917. (1917 was incrementally better than 1915 – only 44 shipwrecks reported in 1917…) The Mariposa had departed Seattle approximately a month earlier, on October 14. It made its way northward, along the way rescuing the passengers and crew of the Al-Ki, a ship that went down off Port Augusta, AK, on November 1. The Mariposa was actually the second vessel on the scene. The first was the Manhattan, a halibut fishing vessel of Canadian registry with a crew of 35. However, as the passengers and crew had abandoned the Al-Ki, the crew of the Manhattan looted the ship and left the scene as pirates. The Mariposa arrived, picked up the crew and passengers, and continued its trip north with its newfound rescues.

Cordova was one of the ports of call on this voyage, and the Mariposa picked up a load of 1200 tons of burlap-sacked Kennecott copper ore to haul to Tacoma. 1917 was right in the heydey of Kennecott production, with the mines in full swing and the very richest ore still being mined. On the way back to Juneau, the ship again encountered a vessel in distress – ironically the Manhattan. In a heavy snowstorm on November 14, the ship hit an uncharted rock near Lituya Bay, AK. The Al-Ki passengers and crew were furious at the pirates and now had the chance to confront them directly, so it was probably good that they were immediately locked up upon rescue. Shortly afterwards, the Mariposa with all three passenger loads aboard docked at Juneau, and the pirates were handed over to authorities.

Having completed business in Juneau, the Mariposa headed to the cannery at Shakan Island to load canned salmon. Shortly after her 3:00am departure from Shakan, the Mariposa met her end. Just off Point Baker at 5:30am on November 18, 1917, the ship found an unmarked reef (now appropriately named Mariposa Reef) the hard way and tore a large hole in the forward hull.

All 265 passengers and crew were rescued, but the ship was in bad shape. At 9:38am, the vessel broke in half near the boiler room, and the stern section sank into deep water. The bow remained firmly stuck on the reef, and remained there for several years. Reports indicate that several loads of salvage were removed from the bow section in 1918-1919. Local fishermen who passed the wreck regularly noted that between April 5 and 6, 1921, the bow section came unstuck and joined the stern deep beneath the waves.

Salvage Efforts and Reality TV

And there it sat – hundreds of tons of Kennecott copper ore – for nearly a century. (The canned salmon might be okay, too, but I’m not trying it first…) The Mariposa lies in deep, cold water with swift currents. The story picks up again with Mark Hargitt, who launched an effort to salvage the ore onboard the Mariposa. And that’s where this gets weird. Mark appeared on Season 5 of the TV show “Shark Tank” back in May 2014, seeking a $250k investment to launch the salvage operation. The “sharks” declined, and referred to his cooler full of salvaged ore samples as “smelly rocks”. Hence the title of this post.

My interest in all of this is from the Copper River & Northwestern Railway angle. I model the CR&NW in N scale, and have always been fascinated with its history. However, being an isolated, poorly-funded ore hauler whose last train ran 82 years ago, very little remains in terms of artifacts.

In one of my regular searches for anything Kennecott (Alaska) or CR&NW-related on eBay, I noticed one of the hunks of ore pop up. Mark was selling it after his Shark Tank appearance. I picked it up for almost nothing considering all the work he went through to get it. I think he was hoping I’d be interested in investing in his venture, but I declined. I just wanted to have this little nugget of history.

Sure, it’s a couple pound chunk of mostly pure copper encrusted by a hundred years of sea varmints, and to your average person it’s just not that appealing. But to a CR&NW enthusiast, to have an actual piece of the rich ore that made the line profitable, hauled out in the heydey years of the late 1910s, it’s an invaluable if ugly piece of history. A tie binding me to 120 years of America’s industrial past.