Introduction

The Isle of Where? The Isle of Man is a small island (roughly 32 miles long by 11 miles across) in the north Irish Sea, located about halfway between the Lake District of England and Northern Ireland. It’s a self-governing British dependency, and the Manx are British citizens. However, it’s not part of the UK or the EU. However, it is part of the UK’s Common Travel Area, so travel between Man and the UK is free of any border control. I went via a flight on now-defunct airline Flybe out of Manchester in September 2017, but there are a number of flights in, and the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company offers ferry service from a number of ports.

How did I wind up there? I had meetings in Atherston (England) the first week in September 2017, and then meetings outside Paris the third week. I had to find something to do with the intervening week, and for some reason I’ve always wanted to visit the Isle of Man. So I did.

At one time, the small island had at least nine distinct railways, along with a number of funiculars. There’s a great Youtube animation of Manx railway changes by year I recommend for anyone wanting to understand the where and when of the island’s rail system.

- Manx Electric Railway (1893-present): Operates 17 miles of electrified double-track 3ft. trolley line from Derby Castle (at the north end of Douglas) along the east coast of the island to Ramsey. Nationalized in 1957 along with the Snaefell Mountain Railway, and continues operating today.

- Snaefell Mountain Railway (1895-present): Operates 5 miles of electrified 3’6″ double gauge track from Laxey (on the Manx Electric) to the summit of Snaefell, the highest moutain on the island. Became part of the Manx Electric Railway Company in 1902, and was nationalized in 1957. Continues operating today.

- Isle of Man Railway (1870-present): The Isle of Man Railway constructed its first line, from Douglas to Peel, in 1873, and its second from Douglas to Port Erin in 1874. Absorbed the Manx Northern in 1904. All of its lines were 3′ gauge and steam powered. At its largest, had roughly 47 miles of trackage. The Douglas-Peel and former Manx Northern St. Johns-Ramsey lines were abandoned in 1974. The remaining Douglas-Port Erin line was nationalized in 1978, and continues to operate today.

- Manx Northern Railway (1878-1904): Built a 3′ gauge line from from St. John’s, on the IOMR’s Douglas-Peel line, to Ramsey in 1878-1879, and a small branch from St. John’s to Foxdale in 1883. The MNR became part of the Isle of Man Railway system in 1904.

- Groudle Glen Railway (1896-1962, 1982-present): Operates 3/4 of a mile of 2′ gauge trackage from Lhen Coan (below Groudle) to Sea Lion Rocks, on the cliff-side above the eastern coastline. Built in 1893 to connect tourists at the Groudle Glen Hotel to various attractions on the coastal headlands. Abandoned 1962. Rebuilt and restored thanks to preservation-minded volunteers since 1982, and still operates today.

- Douglas Bay Horse Tramway (1876-present): Operates 1.6 miles of 3′ gauge double track along the Douglas seaside promenade, connecting the sea ferry terminal on the south end with Derby Castle on the north end. Unique in that the motive power is still draft horses. Currently the most endangered of the still-operating lines, as the city of Douglas threatened to shut the line down in 2016 and is now looking at single tracking and/or shortening it in redeveloping the promenade.

- Upper Douglas Cable Tramway (1896-1929): A 3′ gauge cable car line built to complement the horse tramway lines. The line followed a U-shaped route up and down the steep Douglas hillside between the Broadway and Clock Tower terminals on the promenade. Abandoned 1929.

- Douglas Southern Electric Tramway (1896-1939): The only standard gauge line on the island, the route consisted of 4.5 miles of electrified track between the south end of Douglas and the resort town of Port Soderick. The line was single track. The line was abandoned in 1939 after tourist traffic fell off.

- Great Laxey Mine Railway (1823-1929, 2004-present): A 19″ gauge mine railway that connected the workings of the Great Laxey Mine to the ore washing/sorting areas at Laxey. Originally worked by ponies, the line converted to steam power in 1877. The mine was abandoned in 1929, and the above-ground railway was scrapped in the 1930s. In the 1970s, an archeological survey found an entire ore train intact underground. Using the ore wagon restoration as a starting point, volunteers rebuilt the above ground section between 2000-2004 and it still operates today.

- Funiculars – Yes, technically these qualify as railroads. The Isle of Man had quite a few given its small size:

- The Port Soderick Cliff Lift (1900-1939): Constructed in 1900 to 4′ gauge (recycled/moved from the Falcon Cliff Lift in Douglas) to connect the resort town of Port Soderick with the end of the Douglas Southern Electric Railway on the hillside above town.

- The Douglas Head Incline Railway (1900-1954): Constructed in 1900 to 4′ gauge to connect the ship dock at Douglas Head to the Douglas Southern Electric Railway on the cliffside above.

- The Falcon Cliff Lift (1887-1900, 1927-1990): Built to connect the Douglas Promenade with the Falcon Cliff Hotel some 250′ above. The original line was 4′ gauge and powered by a small engine, and was dismantled and sent to Port Soderick in 1900. The second was built in 1927 to 5′ gauge and electrified, and operated until 1990.

Manx Electric Railway

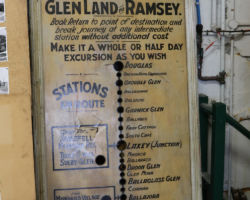

The Manx Electric Railway is a 17.75 mile, double track, 3′ gauge interurban electrified railway that runs up the eastern coast of the Isle of Man. Initially, the line was called the Douglas and Laxey Coast Electric Tramway Company, and construction of the system between Derby Castle (the north end of the Douglas promenade) and Groudle Glen occurred in 1893. By 1894 the road reached Laxey, and by 1899 was completed into the center of Ramsey.

The line’s construction outpaced its revenue, however, and the line defaulted on its debt and was liquidated around 1902. A group of British investors bought the assets of the D&LCET as well as the Snaefell Railway, and joined them together as the Manx Electric Railway Company.

In the post-WWII era, the line struggled for ridership and was eventually was nationalized in 1957. Since then it’s been administered under the Department of Infrastructure, and is now one of four heritage railways owned and operated by the Isle of Man government (Manx Electric, Snaefell, the Isle of Man Railways line Douglas-Port Erin, and most recently the Douglas Bay Horse Tramway).

Until 1998, the MER offered year-round service, but now operates seasonally from March to November when most tourists are on the island and use the line. Buses provide faster, more comfortable, and more reliable service between Douglas and Ramsey for workaday public transportation. (Even I’m guilty of using them once, despite being a die-hard railfan. Buses have padded seats, 1890s trams do not.)

As a note for those not versed in tram terminology, I’ll be using terms like “toastrack” and “saloon” to describe the cars. If you’re like me before this trip and have no idea what any of that means, here’s a quick guide:

- “Toastrack” – So named because the seating arrangement resembles a rack for holding toast. Full-width seats run across the car, and entry/exit to the seats is made through the car sides. These come in open top and roofed varieties.

- “Saloon” – Cars with internal seats and aisles, and doors on the ends. Most are one aisle down the middle, rows of seats on both sides perpendicular to that aisle. Some have bench seats lengthwise along the car and an aisle. These come in all sorts of weird variants like “winter saloon” and “vestibuled”/”unvestibuled”, but I’m just going off what the rosters say on these. I’m not nearly enough of a tram boffin to be able to positively tell you what differentiates one from the next.

- “Tunnel Cars” – Cars that originally had long bench seats lengthwise along the sides, with an aisleway down the middle. For the MER, that’s cars 4-9. These are variants of Saloons.

The Manx Electric Railway Museum

For a few hours on Sunday every week, the MER has a small museum located at Derby Castle that’s open for a few hours every Sunday afternoon in the summer season. It was one of those things that I scheduled other activities around, because I had exactly one shot at it. The weather was ugly (rainy, blustery, and generally cold) on Sunday morning, so I just slept in and then hit up the museum first thing when it opened at noon. From there I rode up to Laxey, killed some time, and then came back and did the Groudle Glen Railway once the weather improved a bit.

The Snaefell Mountain Railway

The Snaefell Mountain Railway is a 3’6″ railway built in 1895 for sight-seers to reach the top of Snaefell, the highest peak on the Isle of Man. The line connects with the Manx Electric Railway at the Laxey station and then winds its way nearly 12 miles and 2000′ feet higher to reach the summit station. While the line has a nearly 10% ruling grade, it’s an adhesion railway – no racks involved.

“But wait!” you’re thinking, “I see a center rail on that thing! Isn’t that a rack system?”

Nope. The center rail is what’s known as the Fell Mountain Railway System, invented in the 1860s by British engineer John Barraclough Fell. Originally it was designed to provide additional traction from a set of wheels clamped on the sides of the center rail, much like a rack railway would use the rack and pinion. However, the Snaefell Mountain Railway only ever used it for braking going downhill. On each car was a set of wheels which would hold the car on the tracks, and also brake shoes in a clamp configuration around the Fell rail. While descending the incline, the clamp could be engaged by the driver to provide additional or emergency braking.

The line still operates using five of the original six tramway cars delivered in 1895. Car 5 burned in 1970 and was basically rebuilt from the frame up, so it’s the least original of any of the cars still in service. Car 3 no longer exists except as a pile of parts at Derby Castle. It was destroyed in a runaway accident on Mar 30, 2016, where it wasn’t properly secured at the summit and took off down grade, derailed just above the Bungalow road crossing, and was destroyed.

That’s not to say the cars operate with 1890s-vintage systems, however. All of the cards all have been rebuilt and modernized over the years in terms of their electromechanical systems, though most (except #5) retain their original bodies. They all received upgraded and modernized electrical systems in the late 1970s, including retrofitting new electrical gear from retired tram cars from Aachen (Germany). This added cars dynamic (resistive) braking in addition to the regular friction brakes and the Fell brake, relegating the Fell rail to emergency use status.

I was a little concerned that I wouldn’t get to ride the line. Another runaway had occurred just weeks before I arrived on the island. On August 4, 2017, car #2 lost its dynamic brakes with passengers aboard, reportedly due to low air pressure. The car ran through the Bungalow crossing at around 44 mph, which is normally (at that time) 12 mph territory. Fortunately the crew used the Fell brake and brought the car to a stop shortly thereafter. (No, I don’t quite understand that either – it seems dynamic brakes should work as long as there’s excitation current and a resistor grid, and air pressure should have nothing to do with it. Perhaps the contactors that change power routing are pneumatic?) Service was suspended until August 12th, but fortunately while I was there, they were running again. That wouldn’t last, however – the Health & Safety folks closed the railway down a week later, on September 25th, 2017.

Note: As of 2019, the cars have now all been outfitted with a fourth, fail-safe brake – an electromagnetic brake shoe slipper that grabs the railhead using magnetic force and brings the vehicle to a stop.

The Groudle Glen Railway

About three miles north of Douglas, on the eastern short of the Isle of Man, lies a small railway that refers to itself as “the line that goes uphill to the sea” – and it’s absolutely correct about that. It’s little in every sense of the word – 2ft gauge and less than a mile long, running from Lhen Coan deep in Groudle Glen uphill to Sea Lion Rocks, the terminal station high on the cliffs above the sea. But the line has has a hundred and twenty four years of history as I write this, and it’s now cared for by a fantastic group of volunteers who have recreated much of what the railway was in its heyday before World War I. Meet the Groudle Glen Railway.

The history of the Groudle Glen Railway goes back to the 1890s, when local businessman Richard Maltby Broadbent leased the area around the Groudle River, intending to develop it as a tourist attraction. He first opened his hotel on the site in July 1893, and only two months later the hotel was connected back to Douglas not only by road but now by the newly opened Manx Electric Railway just out the front door. Walking paths along the river were built through the Glen, and the tourists came.

In 1895, the small zoo was constructed at the coastal end of the Glen to further entice visitors. A small rocky cove was dammed and blocked off with an iron grate, and six sea lions were imported from California (5-6 more didn’t survive transport, depending on the account). Another cage was built on the far side of the cove, with two polar bears housed within. Visitors could look down on the sea lions from a rickety iron bridge that connected the Glen side of the cove with the polar bear enclosure. Eventually two brown bear cubs, chained to prevent their escape, were added so that visitors could have their photos taken with them. By any modern standard, it was bleak, cramped and appalling for the animals, but in the Victorian era it proved immensely popular. A two-foot gauge railway was constructed almost immediately in the winter of 1895-1896 to shuttle visitors from near the hotel – at a spot in the Glen known as Lhen Coan – down to the headlands to visit the attractions. The line would be just slightly under a mile long, have a single passing siding, and would become known as the Groudle Glen Railway.

The railway opened to the public on May 23, 1896 using a tiny 2-4-0T named “Sea Lion” and three passenger coaches. Nine years later, to accommodate the large number of visitors, a second locomotive – another diminutive 2-4-0T aptly named “Polar Bear” – and more coaches were added. Business boomed, with summer days seeing up to 40 trips over the short route. Operations continued until World War I, when both the zoo and railway were closed for the duration of the war.

It took a couple years after the war ended, but in 1920 the railway and zoo reopened, albeit without the polar bears. The steam locomotives were shot, having been run hard for decades. The glen’s new owner, Alfred Lusty, decided to replace them with a pair of 0-4-0 battery-powered locomotives bearing the same names as their steam predecessors. Both proved to be troublesome contraptions, prone to derailing. After one took an unexpected excursion over the hillside, they were made into 2-4-2s. The underlying technology, though, just wasn’t up to the task, with battery technology being relatively primitive in that era. Both steam engines were returned to the manufacturer in 1926 for a full overhaul, and by the end of the 1920s, the battery locomotives headed for the scrap heap. Steam once again ruled the line through the 1930s.

With the start of WWII in 1939, the zoo and railway were once again shuttered. The zoo’s closure was permanent this time, with the sea lions released into the open ocean. The railway, on the other hand, slowly restarted operations once again in 1950. A landslide under the right of way had left the track impassible between the headlands siding and Sea Lion Rocks, but irregular operations were made using Polar Bear between Lhen Coan and the end passable track until 1962. At that point, it looked to be the end of the small railway. Both steam engines were removed and the facilities were slowly removed, vandalized (apparently one coach wound up going down the hill on its side), stolen, or just allowed to fall into disrepair.

In 1982, the Isle of Man Steam Railway Supporters’ Association undertook restoring the tiny line. By 1986, the line from Lhen Coan to the landslide was once again operating. In 1987, Sea Lion was returned to service following a complete restoration. By 1992, rails once again reached the original terminus at the cove. Volunteers began construction of a replacement station at Sea Lion Rocks in 1999, with the interior finally completed in 2003. In 2010, the station was upgraded to include restrooms and power, so that it could serve a tea room for visitors. Beautiful new hardwood coaches were constructed in 2014-2016. Currently, the line is currently building a modern replica of 2-4-0T “Polar Bear” that will be known as “Brown Bear”, since the original is owned by the Amberley Working Museum in West Sussex, UK.

For visitors, the railway typically operates a very limited schedule – typically Sundays and some Wednesdays. Be sure to check their website for details.

Isle of Man Railway

The Isle of Man Railway was the most extensive railway on the island, eventually having three main routes totaling some 47 route miles. The original route, from Douglas to Peel, opened in July 1873. The Douglas-Port Erin line, which we’ll see below, opened a year later in the summer of 1874.

In 1904, the IMR took over the Manx Northern Railway, which connected with it at St. John’s on the Douglas-Peel line. The Manx Northern had built a line from St. John’s to Ramsey in 1878, and a mining branch from St. John’s to Foxdale in 1886 (nominally the Foxdale Railway, but always operated by the MNR). When the two merged, the IMR system reached is maximum size.

The IMR, right up until the end of regular operations in 1965, was not fundamentally a different railway than when service had begun nine decades prior. Because of the unique geographic and economic circumstances of its environs, it never really had to embrace modernization. It was never forced to do so. The island was small and the trips were short. All of its freight wagons were tiny and two-axled, and many dated from the early days of the line. Vacuum brakes, still in use today, weren’t even fitted to all stock until 1927. Its newest motive power was from 1926, but the mass of its fleet was pre-1900, although many had received reboilerings and were all well maintained. The line’s very first locomotive ran right up until the end of regular operations in the 1960s. I suppose there are many other insular examples of railways like this off the beaten path, but from a North American point of view it seems incredibly odd and special.

That’s not to say the line wasn’t extensively used. Regular service was about 4-5 trains per day. In the 1930s, reports have the IMR running as many as a dozen trains each way on each line during the busy summer season. However, as the island’s road system improved in the post-WWII era, the railway’s fortunes declined. Freight was just much more effectively handled by trucks given the island’s tiny size. However, passenger numbers held up well until the late 1950s. In 1957, over a million passengers rode the IMR. It was the last year that number would be reached. By 1960, passenger numbers were so low that winter service ceased on parts of the system. Then on Nov 13, 1965, the railway shut entirely. Nothing at all operated in 1966, save apparently a train for the TT races.

The Manx Government set up a committee to study the issue, which came back with a recommendation that at least Douglas to Peel be maintained as a tourist attraction. Archibald Kennedy, 7th Marquess of Ailsa, stepped in and agreed to lease the system for 21 years, with an option to exit the agreement in five years if he could not turn the system’s fortunes around. He opened the system with an ambitious timetable of operations in 1967, operating all three main lines. In addition, the railway tried to bring back freight service, experimenting with intermodal and fuel shipments. Service was cut back in September when passenger counts failed to materialize, and the operation struggled through 1968 with similarly reduced schedules.

By the end of 1968, it was clear that the bold rescue effort had failed. The last passenger train to Ramsey ran on Sep 6, 1968, and the last train to Peel ran the following day. Neither route would see another revenue passenger train. The lsat revenue train of any type, an oil train headed from Peel to the Ramsey power station, ran in April 1969. Both routes would be scrapped out in 1974-1975.

The Douglas-Port Erin line fortunately had a slightly different fate. It continued to operate into 1969 and 1970, though unsustainably, under the lease agreement thanks to a partnership with another organization called the Isle of Man Victorian Steam Railway Co. In 1971, Kennedy exercised the five year option to exit the lease. From there, the Victorian Steam Railway Co. partnered with the Tourism Board for the additional funding needed to operate the line. By 1975, the government shut off the funding, and operations were restricted from Port Erin to Castletown using another small private grant. In 1976 they were back as far east as Ballasalla, and in 1977 they finally returned to Douglas.

Finally, in 1978, the government realized they were on the brink of losing an invaluable historic asset, and remnants of the IMR were sold to the government for £250,000. The line was then run by the Manx Electric Railway Board, which eventually became the Heritage Railways department of today.

Today’s Douglas-Port Erin operation looks unsurprisingly different from the line did during peak years. While certain compromises have been made to modernity and safety (such as crossing lights instead of manual gates), the railway still runs with its century old locomotives and cars over the same route they’ve trundled their entire existance. The line and equipment are in exceptional shape these days, and it’s clear that this unique little capsule of railway history is valued and will be for years to come.

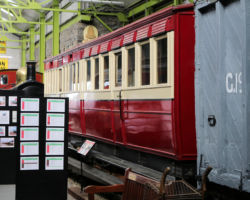

I took a day trip over to Port Erin and back while I was there. One of the key things I wanted to do was visit the railway museum next to the station, in the old railway goods shed. It was founded in 1975 to save a few of the artifacts rapidly disappearing as the railways were being scrapped. It’s open most days that the railway operates, and is an excellent way to spend an hour or two in Port Erin.

Once I’d finished looking about in the museum, I wandered over to one of the local pubs for some lunch, wandered around town for a bit, and decided that it was a pretty nice day except right by the ocean. A good day for a quick hike, in fact. Instead of re-boarding the train to Douglas as Port Erin, I walked down to Port St. Mary, the next station halt east. I thought about walking to Castletown to catch the meet instead, but seeing as I was getting on the last train of the day back to Douglas I didn’t really to chance missing it.

I didn’t include many “out on the line” pictures from the IMR. It’s a tough line to photograph even if you have a car or bike, just because it runs between tight fences and hedgerows for much of the journey, and is typically rather far from roads. Plus, you’ll only get a couple trains a day either direction. On foot, as I was, I’d say it’s tough to impossible to get many decent action shots if you only have a day or two to devote to it. If you were sufficiently clever and athletic (which I fail a bit at both), you could probably string together bus transportation and a bit of hiking and get it done. I’d say at the end, a car or at least a bike would be a better option if you want photos out on the line.

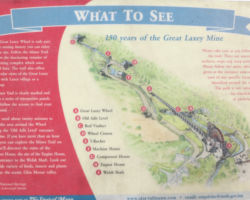

Great Laxey Mine and Railway

The mountains between Laxey and Snaefell were rich in mineral wealth, primarily lead and zinc ores, but with a significant minor fraction of copper, silver, and iron. Records of lead mining by prospectors or small groups go back well into the 1700s. A particularly rich deposit, located just above Laxey proper, was located in the early 1800s and the Kirk Lonan Mining Association was set up to work the mine in 1822. This would become the Great Laxey Mine in 1862. Shafts would eventually reach down 2200 feet into the earth, following rich veins of ore. At its peak around 1875, the mine employed 800+ miners and turned out 2400 tons of lead, 12000 tons of zinc, and 500 tons of copper annually, making it one of the richest mines in the British empire. In fact, this single mine was responsible for approximately half of the UK’s entire zinc production.

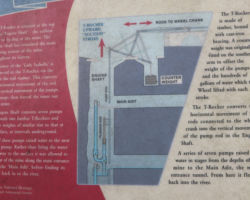

The mine always had water problems. Even in the early years, a 1833 flood from the river coming down the valley flooded the mine works and it took until early 1834 to dry them out again. The Isle of Man has no coal reserves, so conventional steam engine-powered pumps would have been expensive to operate on imported fuel. The solution designed in 1854 by Robert Casement was an enormous water wheel, harnessing the power of the stream that flowed down through the mine works and so frequently caused it trouble anyway.

The Laxey Wheel, otherwise nicknamed “Lady Isabella” after the wife of the Lieutenant Governer, was 72.5′ in diameter. Water was collected in a cistern far uphill, and piped down and up the top of the tower. From there, it flowed into buckets which turned the great wheel. The wheel then turned a crank, which transmitted power via a long wooden shaft some 600 feet back to the “engine shaft”, where a rocker arm turned the power shaft 90 degrees and sent it deep into the earth, where it powered a series of 7 pumps that could lift 250 gallons per minute out of the depths of the mine.

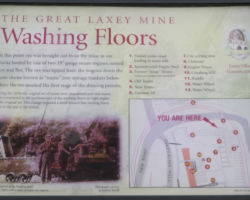

Unlike many mines, there was no nearby smelter. Remembering that the Man has no known coal reserves, it was cheaper to export the ore than import the fuel. However, the mine did have the early 1800s equivalent of a concentrator to minimize the amount of worthless rock being shipped. This was known as the “washing floor”, and was located down the Laxey River valley from the mine itself. Starting in 1827, ore would be hauled out of the mine’s main adit on a horse-drawn 19″ gauge railway down to the washing floor. At that point, the ore would be dumped into a large ore bunker to be processed.

The processing was highly manual, and employed about 300 people in the peak years. The first step involved manually picking out any waste rock by hand and discarding it. From there, the ore was fed to a crusher (powered by the Laxey water wheel) and once again, the waste rock was removed by hand from the crushed output. At that point, a “jigger” would sort the ore out by its greater density. Fine material from that process would then go through final step, known as a “buddle“, would separate out fines that had metals in them from waste rock. Once all the ore had been concentrated and the waste rock discarded, the ore was then hauled down to waiting ships by horse cart.

By the 1870s, the mine sought to increase the efficiency by replacing the ponies pulling the ore carts from the mine to the washing floor with a pair of small steam locomotives – Ant and Bee. In order to work the tiny mining adit, these engines were minuscule. They resemble a horizontal 55-gallon drum on two axles, with a footplate on the rear for the operator. It’s hard to find a locomotive that even the IMR’s small 2-4-0Ts would look down upon, but these two would fit the bill. These two were tiny but mighty, though. Each could pull 6-7 ore carts out of the mine and down to the ore hoppers, and they worked so well that they remained in use right up until the mine ceased operation in 1929.

Unfortunately, in the early 1930s, everything was scrapped. The mining equipment, the railway, the engines, and the cars. The wheel was only preserved because local businessman Edwin Kneale purchased and preserved it. The Manx government purchased it from Mr. Kneale in 1965, and turned over care of the wheel to Manx National Heritage in 1989.

The railway, on the other hand, follows a somewhat different story. Everything really was scrapped in the 1930s. Well, everything above ground anyway. Apparently in the 1970s one of the adits was cleared out for some archeological work, and a complete rake of six ore wagons was found. The wagons were removed and restored, and their existence spurred interest in restoring the above-ground section of the line. (Note: the ore wagons on site are not the historic versions, but apparently replicas. The historic wagons are in museums around the island, I’ve read.)

Between 2000-2004, volunteers rebuilt the above-ground line from the washing floors up to near the main adit entrance, a distance of about a quarter mile. Replicas of both Ant and Bee were purchased, and a pair of non-historic carriages were built for passengers. Unfortunately the line only operates on Saturday, and because my flight in on Saturday was significantly late, I didn’t get the chance to visit while they were operating.

Douglas Bay Horse Tramway

It’s tough to choose the most unique or historic line on this island, because they’re all such wonderful little anachronistic oddballs. But if you really forced me, I’d probably pick the Douglas Bay Horse Tramway. There are only a few operating horse-powered tramways left in the world, and most of them are either modern creations or recreations of a tramway that long ago stopped operating. The Douglas Bay Horse Tram is the real deal, having operated every season (except the WWII years) since it was builtin 1876.

The double track 3′ gauge line runs the length of the Douglas promenade, from just outside the Steam Packet Company’s sea terminal on the south end to Strathallan on the north. (Strathallen is the line’s shop and storage depot, and is immediately adjacent to Derby Castle on Manx Electric.) The line is, as it always was, completely powered by draft horses – primarily Clydesdales and Shires these days.

At the time I visited in 2017, it was also probably the most endangered of the island’s lines. While recognized as an important piece of Douglas’ history, it was also a tremendous money sink, estimated to have lost £263,000 in the 2015 season. The Douglas borough government, which has operated the line since 1900, decided they could no longer afford the operation and announced there would not be a 2016 season. Fortunately, the Isle of Man government voted to fund the line’s operation for 2016-2018 on a trial basis. There was also significant pressure during the promenade redevelopment that either the line be single-tracked, or moved out of the way of general traffic. Traffic is already brutal along the Douglas promenade at peak times, and a double track horse tram right down the middle of the road definitely doesn’t help.

It appears that the IoM government now considers the trams an important part of their heritage railway system. In 2019, the tracks were being rebuilt right where they’ve been for decades. They’ve also just completed (as of late March 2020) a new car depot at Strathallan to replace the old, worn out facility. For now, it looks like the Douglas Bay Horse Tram is safe and on a good path for many more years of operation.

Most everything in this trip report was shot with dad’s Canon 7D II and Canon 24-105mm f/4L. He passed away about six months before this trip. Dad would have loved this place, so it seemed a fitting tribute to take his camera instead of mine.

This work is copyright 2024 by Nathan D. Holmes, but all text and images are licensed and reusable under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. Basically you’re welcome to use any of this as long as it’s not for commercial purposes, you credit me as the source, and you share any derivative works under the same license. I’d encourage others to consider similar licenses for their works.