At the south end of Lake Okeechobee exists a unique railway system, unlike anything still operating in the United States. US Sugar farms sugar cane on over 200,000 acres in the area, and operates nearly 300 miles of railway to support their immense operation. It’s the last of its kind in the United States, and one of only a dwindlingly small number of sugar cane railway systems in the world.

Last January, Trains Magazine sponsored the first photo charter I know of being run on US Sugar’s rail system, using their newly restored steam locomotive. There’s a lot of history to be told here, much of which I had to learn myself going down various rabbit-holes trying to understand how all of the various routes and industries fit together into what today looks like a unified system. There’s the story of the locomotive, the story of sugar cane agriculture, the story of US Sugar as a company and as a railroad system, and how all of these came together to lead up to three very special days at the end of January 2022.

The Story of FEC 4-6-2 #148

FEC 148 is a lightweight 4-6-2, originally built for the Florida East Coast Railroad by ALCO back in 1920. Its usual assignment was running freight and passengers over the FEC’s Key West Extension between Miami and Key West, until the line was destroyed by the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. 148 was retained by the FEC until June 1952, when it was sold to the US Sugar Corporation.

US Sugar used 148 (along with sister FEC 4-6-2s 98, 113, and 153) to harvest sugarcane from the fields surrounding the town and haul it back to the company’s various mill. That lasted for over a decade, until 148 was USSC’s last operating steam engine. But the era of diesels had come, and 148 was sold to Sam Freeman in September 1968. From there it worked on the Black River and Western Railroad in New Jersey until 1977, when it went out of service. Upon Freeman’s death in 1983, the engine went to the Valley Railroad of Essex, CT, and then on to a private owner in Traverse City, MI in 1988. In March of 2005, Don Shank’s Denver & Rio Grande Historical Foundation – the owners of the former D&RGW Creede Branch in Colorado – purchased the engine for potential restoration and excursion service. The engine remained stored near Don’s yard in Monte Vista, CO, until 2016, when it was sold back to US Sugar for restoration.

The engine arrived in Clewiston by rail in mid-December 2016, and restoration work began immediately using FMW Solutions, LLC, as the primary contractor. The boiler was lifted off the frame in January 2017 for its overhaul, while the frame and running gear were simultaneously rebuilt. The work was extensive – in a Trains magazine interview with Shane Meador of FMW, he states that entirely new pistons, valves, side rods, main rods, crank pins, tires, and driving boxes needed to be fabricated. In addition, the boiler needed extensive work, with a new first course and smokebox being fabricated and the firebox completely rebuilt. The tender was also largely shot, and had an entirely new tank fabricated to sit on top of the rebuilt frame and trucks. With all of that and much more completed, the boiler went back on the frame in the spring of 2019. By December of 2019, the locomotive was reassembled enough to steam up. Jacketing and paint work then commenced, and was ready for test runs by April 2020.

COVID put a pause on plans for a few years, but the locomotive will form the basis of the Sugar Express, a train ride operating over the company’s lines. It’s a US Sugar public relations effort to engage with the community about sugar farming in south central Florida.

As a side note, FEC 148 will be joined by Atlantic Coast Line 1504, another ALCO 4-6-2 built a few months before 148. The locomotive was retired by the ACL in 1960 and preserved in front of their offices in Jacksonville. In 1986, CSX donated the engine to the city, who moved it to a new display location outisde the convention center. The city wanted to be rid of the engine, so in 2021 they donated it to the North Florida Chapter of the NRHS, who had taken care of upkeep and cosmetic work on the engine for years. The NRHS chapter then turned around and sold it to US Sugar for restoration. It’s expected to be completed somewhere around 2025.

The Story of Sugar Cane

I’ll be honest – before going on this trip, I had only the roughest idea how sugarcane farming worked. I knew there was something about growing some really big grass, then some burning, then some turning the cane juice into sugar. Yup, that’s about it.

Planting is still done manually. First, the field is tilled and furrows are cut into the soil. A tractor pulls along a wagon loaded with fresh cane, and workers follow behind cutting the cane into 12-18″ lengths and tossed into furrows horizontally. It’s then covered with soil. These cuttings eventually take root and will grow into a plant with several new stalks.

After about 12 months, the cane is ready to harvest. At this point, processes diverge. Some companies harvest the cane still green, using specialized harvesters that separate off the unwanted parts of the plant and return them to the field. Others will burn the field first and then harvest what remains, again using mechanical harvesters. The burning eliminates much of the waste foliage and drives out much of the hazardous wildlife, but creates significant air pollution in the process. Florida seems to be a mix of both processes currently, though internationally many countries have restricted burning due to the associated health hazards the smoke poses, and there is pressure to do so in Florida as well.

Once the cane is cut, it gets loaded into wagons pulled by tractors that are paralleling the harvesters through the field. The tractors then run the wagons back to loadout points when they get full, and the cane gets transferred either on to rail cars or on to trucks. One acre yields about 40 tons of harvested cane, or about one rail car worth.

Cane deteriorates very quickly once harvested. What you want out of the cane is the sucrose. However, the longer it sits, the more of this sucrose is converted to dextran molecules of various length by naturally occuring bacteria. Dextran not only represents the loss of the sugars the company is trying to extract from the plant, but also can be a troublesome impurity to remove. The US Sugar crews on the train stated the goal was obviously to move the cane as quickly as possible, but eight hours from harvest to mill was about the maximum tolerable limit.

Once at the mill, the cane is dumped into a giant crusher and the juice extracted. The juice is clarified to remove solids and then boiled to remove excess water. Once it reaches saturation, sugar begins to crystallize out. This sugar requires additional refining and purification to remove impurities, but is essentially close to the end product. The waste fiberous cane material is known as bagasse. It gets burned within the plant’s boilers to create high pressure steam that provides both process heat and sometimes electricity for the plant, making the mill largely energy self-sufficient.

The Story of US Sugar

The short version of the story of Clewiston and US Sugar starts with John and Marian O’Brien from Philadelphia. John and Marian’s first husband had partnered to buy and operate a 2000 acre farm near Moore Haven in 1916. Marian’s husband had passed away unexpectedly, but she and John carried on with the project. The two eventually married, and John, a captain in the National Guard, was called up to serve in Europe.

After the war, they partnered with Alonzo Clewis, a successful banker and businessman from Tampa. Together, they purchased large tracts of land at the south and west end of Lake Okeechobee in 1920 with the intention of raising winter vegetable crops and developing real estate. The three laid out a town and named it Clewiston, on honor of their new business partner. They also chartered the Moore Haven & Clewiston Railroad to connect their new community to the existing Atlantic Coast Line at Moore Haven.

Bror Dahlberg was the president of Celotex, a company that made a composite sheathing and insulating board out of sugarcane bagasse fibers. By 1924, the Louisiana sugar cane industry that supplied their raw material was faltering and Celotex sales were booming. Consequently, Dahlberg went in search of new lands to convert to sugarcane production. After domestic sugar shortages during World War I, the government was explicitly encouraging the development of sugarcane farming in the Everglades region south of Okeechobee. The O’Briens’ plans for real estate development and farming had not panned out, and the three partners were looking to sell. Dahlberg thought their holdings looked like a fantastic investment to provide raw material to his growing company.

Dahlberg set up the Southern Sugar Company in 1925 and bought some 125,000 acres in these newly drained lands, including the O’Brien and Clewis property. However, a run of crop failures from bad weather – hurricanes in 1926 and 1928 – as well as the onset of the depression drove the new company to bankruptcy in 1931.

Charles Stewart Mott – an industrialist from Detroit and an executive at General Motors – stepped in and set up the United States Sugar Corporation to buy up the assets. Over the years, US Sugar has modernized and expanded to 230,000 acres, but is still largely the same company today. It remains privately held by Mott’s family foundation and spin-offs, as well as by the employees and the company pension fund. They still do what they’ve always done – sugar – to the tune of 700,000 tons per year, and provide a large number of jobs in the region. However, with their land holdings and agricultural experience, they diversified in the 1970s and 1980s as many sugar users switched to corn syrup. As a result, they also grow half of Florida’s sweet corn and produce 90 million gallons of orange juice every year. That, of course, is in addition to running a pair of railroads to support their business, which is what we’ll be focusing on.

The Story of the USSC System

One of the more confusing things about this railroad is that it’s really two railroads, both owned by US Sugar. One – the South Central Florida Express – is a common-carrier shortline that’s part of the US railroad system. The other is the US Sugar Railroad, an industrial plant railroad and used for harvesting and transporting sugar cane to the mills.

The South Central Florida Express

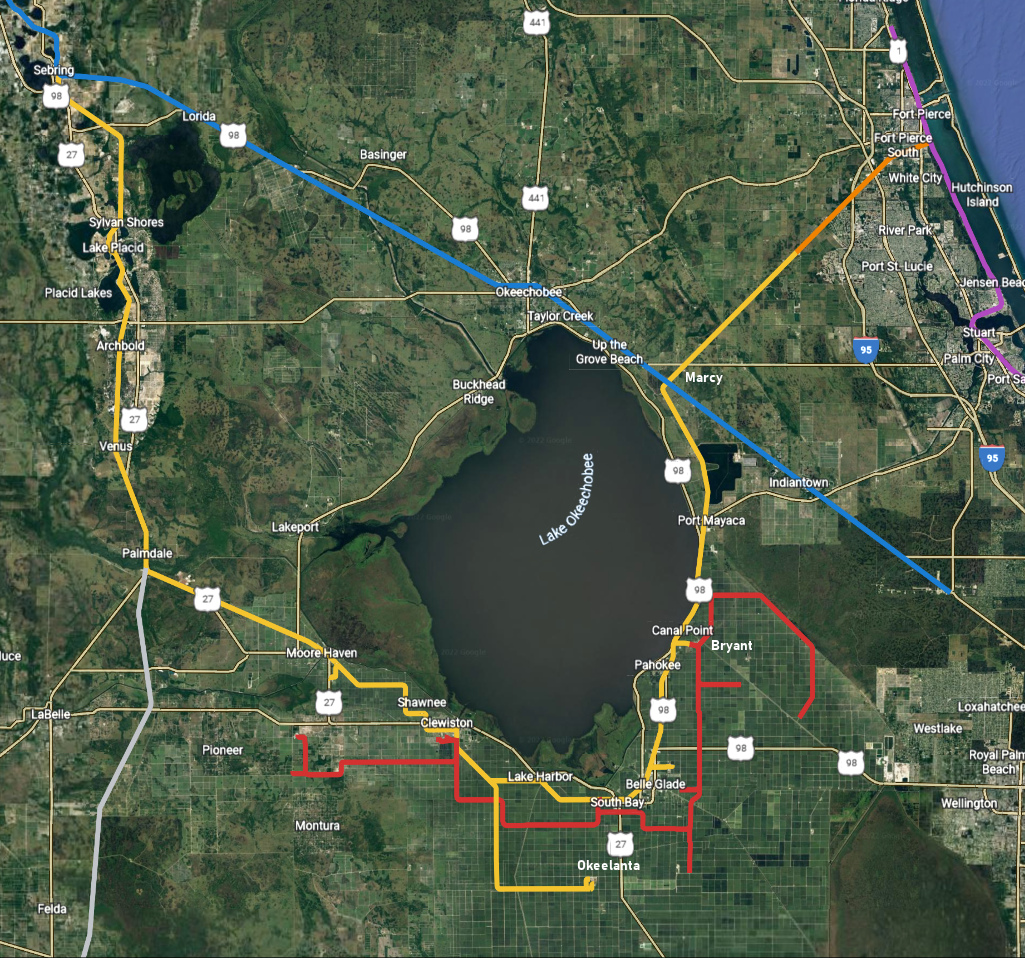

Let’s look at the common carrier side first, the South Central Florida Express or SCXF. (No I didn’t transpose the last two characters – reporting marks ending in X are reserved for non-railroad owners, so as a railroad, they had to end with some other letter.) Its lines form a giant horseshoe around Lake Okeechobee, but the two halves of the shoe have very different histories.

The western half of the horseshoe extends from the CSX interchange at Sebring, FL, down to Palmdale, Moore Haven, Clewiston, and finally ends at Lake Harbor, FL, with a branch running down to Okeelanta.

Originally this line was constructed as the Atlantic Coast Line Haines City Branch, starting in 1912 in its namesake town where the line diverged from the Sanford-Tampa ACL mainline. The initial branch went as far south as Sebring, FL. Between 1916-1921, the line was extended to Immokalee in segments. In 1918, a branch was constructed to the east, leaving the Haines City Branch at Harrisburg and extending to Moore Haven. Around the same time, Moore Haven & Clewiston Railroad was chartered by Clewiston’s founders to built the section between the ACL in Moore Haven to their new holdings in 1920. The line was completed in 1921 and shortly thereafter absorbed into the ACL.

On the south coast of Florida, a group of investors had started a grapefruit orchard near Deep Lake, and had built a railroad to the coast at Everglade (later Everglade City) in order to get their product shipped to market. This Deep Lake Railroad caught the eye of the ACL management, and they purchased it in the 1920s. The line was extended from Immokalee to Deep Lake, connecting their new purchase, and the Deep Lake Railroad was rebuilt to ACL standards. Everglades would become the ACL’s southernmost station, with the first trains arriving in 1928.

The Clewiston branch was extended a few more miles in 1929 to connect with the FEC’s Kissimmee Valley Line (later known as the K-line) at Lake Harbor, with a branch running down to Okeelanta.

The section from Palmdale / Harrisburg down to Everglades City on the coast became the Immokalee Branch. The initial abandonment at the south end in 1958, dropping some 22 miles off the line from Everglade to a rock quarry Sunniside. In 1969, the line became part of Seaboard Coast Line as a result of the ACL-SAL merger. The SAL had a parallel route to the northern part of the line (their Florida Western & Northern Railroad, built in 1925-1927 to connect the SAL to West Palm Beach and Miami), and almost immediately the old ACL was severed at the Sebring crossing. That left the branch to Clewiston and Immokalee now served off the former SAL, starting at Sebring.

By 1984, the branch had been abandoned back to Immokalee, and then from Immokalee to the junction to the Clewiston branch at Harrisburg / Palmdale around 1989. That left only the Sebring-Lake Harbor section, along with the short stub to Okeelanta. Even it was in poor condition – the entire route was down to 10mph, suffering from decades of deferred maintenance. CSX was in the process of spinning off these unwanted branch lines, and in 1990 the remaining 87 miles of track went to the Brandywine Valley Railroad, who operated it as the South Central Florida Railroad. The line’s poor condition was not helped by a new owner with shallow pockets, with derailments and poor service the inevitable result.

In 1994, the line’s primary customer – US Sugar – set up South Central Florida Express, Inc, with the intention of acquiring the line and assuring future quality service. It was set up as a separate company kept at arm’s length to avoid regulatory concerns, because the line also serves USSC’s competitors.

The eastern half of the SCXF common carrier “horseshoe” extends from Lake Harbor up the FEC’s K Branch to Fort Pierce, on the FEC mainline. The line was originally constructed as the Florida East Coast’s Okeechobee Branch (also known as the Kissimmee Valley Line, K Line, or K Branch), starting at Maytown in 1911 and reaching Okeechobee in 1915. By 1929, the FEC extended the branch around the east side of the lake to Lake Harbor, where it connected to the ACL. There was consideration of extending the line on to reconnect with the FEC main at Hialeah – near Miami – to provide an alternate route, but the plan never moved beyond the idea stage.

The K Branch got a significant change in the 1940s. The anticipated agricultural traffic on the long line between Maytown and Marcy never materialized. In order to bypass some 152 miles of branchline trackage, the FEC opened the “Glades Cutoff” in 1947 between Fort Pierce on the coastal mainline, and Marcy on the K Branch.

In 1998, SCXF obtained a lease from the FEC over the ~70 miles of trackage between Lake Harbor and Fort Pierce. SCXF currently handles all business from Lake Harbor to Cana, and their trains run via trackage rights into the FEC’s Fort Pierce yard for interchange.

The US Sugar Railroad

The second system – accounting for 120 miles of track and growing – is USSC’s private industrial railroad. It is not a common carrier, and is used almost exclusively for transporting cane from the fields to the the mills. I say almost, because USSC has a few side businesses – one of which is Southern Gardens Citrus, which produces 90 million gallons of orange juice each year, and was recently connected into the USSC plant railway at the far west end. (Some people list their reporting marks as USCX, some as USSC, and then there’s USSZ is painted on their crossing cabinets. For here, we’ll just call them USSC.)

With recent extensions, the line is now continuous all the way from the Southern Gardens Citrus plant on the west (south of Moore Haven) over through the fields south of South Bay and Belle Glade, up to Bryant, with a spider web of branches reaching out to numerous cane loading points in the fields.

The two systems interconnect at a couple of different locations – at the Clewiston mill, obviously, but also west of South Bay and north of Pahokee.

Operations

The main shops and yard for the system are located at Clewiston. While the engine house is right out along a public street, the yard is buried in the mill property and generally inaccessible.

SCXF runs a somewhat predictable pattern year round. There’s a daily turn from Clewiston to Fort Pierce, a near daily turn from Clewiston to Sebring, and a Clewiston local that services the customers from Moore Haven to Belle Glade.

Outside of sugarcane harvest season (October to April, basically), the USSC industrial side of the railroad is rather dead. However, come October, the railroad springs to life with cane locals running every which direction. Once cane is cut, it needs to arrive at the mill in eight hours to maximize sugar recovery. Locals run to wherever they’re loading, day and night.

That’s not to say traffic on the SCXF side doesn’t increase during harvest. There are numerous cane loadouts along the SCXF, and they all get busy. SCXF also starts running multiple daily Bryant Turns during harvest, which are the “big” cane trains on the line. The Bryant Turns will take large cuts (70-100 cars) of cane cars from the Clewiston mill east to the Bryant Yard (north of Pahokee, on the former Bryant mill property). Locals break the big cut into smaller groups of empties and take these cars out on the USSC lines to be loaded. Once loaded, the locals converge back on Bryant where the small cuts of cars are put back together, and SCXF then takes it out on the mainline and expedites it back to the mill at Clewiston.

SCXF and USSC both move right along, often pushing 40mph where track speed allows. All power is FRA-compliant so that locomotives can move seamlessly between the two systems. The cane car fleet consists of about 800 cars. Many of these have been hauling cane for decades and appear to be purpose-built, but have been modernized with features like modern roller-bearing trucks for safety and reliability. Some of the more recent additions to the fleet appear to be older boxcars and such that have been cut down and modified. The cane cars have three large doors on one side, and the dumpers at the mill tilt the car to a 45 degree angle to open these doors and dump out the cane.

More Information

To learn more about the history and operation of these two unique railroads, I recommend the following three sources, which have been invaluable in trying to understand the history of this unique operation:

- The Railroads of U.S. Sugar: History Through the Miles by Barton Jennings

- “Sugar Rush in South Florida” by Barton Jennings, Railfan & Railroad Magazine, November 2020 page 52.

- “100% Pure Cane Railroading” by Scott A. Hartley, Trains Magazine, December 2015 page 24.

- “A Sweet Ridge No More?” by Frank Kyper, Trains Magazine, September 2009 page 44.

Friday, January 28, 2022

Getting out of Denver on Thursday night proved to be challenging. I was supposed to leave around 5pm. We all boarded the flight, but after we pushed back, the flight crew found something they didn’t like and returned the flight to the gate. Everybody out! They thought they’d found a replacement aircraft, but something with that one didn’t pan out either. Finally, around 9:45pm, we got yet a third aircraft, and were finally underway just before ten. That put us into Fort Myers somewhere around 3am if I recall correctly, which meant I didn’t get my rental car and to the hotel until almost 4. That still left me ninety minutes from Clewiston, the center of the universe for the next three days.

Friday morning was supposed to start with a test run at 8am for the steam crew and for the Trains Magazine folks (so, Jim & Cate Wrinn, Kevin Gilliam, and others) to figure out the plan for the next day.

Saturday, January 29, 2022

Saturday started off with some wonderfully cold weather – about 34 degrees – and thankfully perfectly clear, unlike Friday’s gloom. Okay, so not wonderful for Floridians, but wonderful for steam effects and for making the gators far too slow to eat any wandering railfans.

The train left around sunrise, at 730am. The plan for the day was to work down the Okeelanta Branch, since there was no scheduled traffic on the line that day, and thus we’d be out of the way of revenue traffic. With cane traffic running heavy on almost all of the other lines, this was ideal. Plus, US Sugar had given us use of a small cut of cane cars, so we could have a realistic-looking cane freight for the day (well, assuming you could crop out the passenger cars at the end).

Sunday, January 30, 2022

Sunday was another cool, clear morning. Today we’d be running north over the old ACL from Clewiston up to Palmdale, getting far enough north that we’d be out of the cane fields and therefore out of the way of any cane traffic. Unlike Saturday, there was no turning facility in the stretch of track we would be using, so we left Clewiston running tender first.

So Long, Jim Wrinn

On a sad note, this trip would be the last time I’d see my friend Jim Wrinn. Jim and I crossed paths a number of times over the last fifteen years, since just slightly after he became editor at Trains. I first met him in person when he came out to be the guest speaker at the Rocky Mountain Railroad Club’s 75th anniversary banquet. I’m a relatively nobody – just another railfan with a camera – but it always amazed me that Jim would always remember me and we’d pick up whatever conversation like no time had passed, despite the fact it was usually a year between running into each other. Ever the gentleman and scholar, Jim was always an ambassador for our hobby and a source of great stories and deep knowledge. Even while fighting that all-to-short 14 month bout with cancer, he was always upbeat and enthusiastic, even if exhausted. I’m honored that I got to spend the time I did with you that I did, and those memories I will always cherish.

This work is copyright 2021 by Nathan D. Holmes, but all text and images are licensed and reusable under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. Basically you’re welcome to use any of this as long as it’s not for commercial purposes, you credit me as the source, and you share any derivative works under the same license. I’d encourage others to consider similar licenses for their works.